SPOTLIGHT ON…MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY

Grand daughter Tonia Guerrero writes about the making of this powerful film.

Before Frank Lloyd became a Hollywood silent screen villain in 1912, he used his strong singing voice and comic timing on vaudeville stages in London, Canada and eventually, California. He moved easily from acting and script writing to directing….westerns, dramas , romances, shorts, science fiction, a documentary, war stories, histories, mysteries, melodramatic comedies, a thriller, crime stories, a biography, a fantasy, a fund-raiser for the war effort, even a film noir and a musical. And by the end of his career in 1955, he had acted in, written, directed and/or produced more than 180 films, was President of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences 1934-35 and a founder of the Directors’ Guild.

The lure of the sea, the open ocean, a sailor’s life, and Her Majesty’s ships began as a child for Frank Lloyd while watching his mechanical engineer father install turbines and engines in all sorts of boats, including the Tall Ships. This job took the Lloyd family all over England and Wales and Scotland until an engine accident forced the family to settle down in Shepherd’s Bush outside of London where they bought a pub.

Besides this 1935 epic, Mutiny on the Bounty, Frank Lloyd searched for stories about ships and the power and mystery of the sea: as an actor The Sea Wolf, Captain Kidd, and as a director, The Sea Hawk, Winds of Chance, The Eagle of the Sea, The Divine Lady, Weary River, Cavalcade, Rulers of the Sea and the merchant marine saga, This Woman is Mine.

With the help of uncredited producer Irving Thalberg, Director Frank Lloyd convinced the M-G-M’s chiefs in 1934, in the midst of the nation’s great economic depression, to budget almost $2 million to the making of the film. They knew that this would be the company’s most extravagant movie of the year; it would follow up on the escapism success of the books and play up the giant scope of the production.

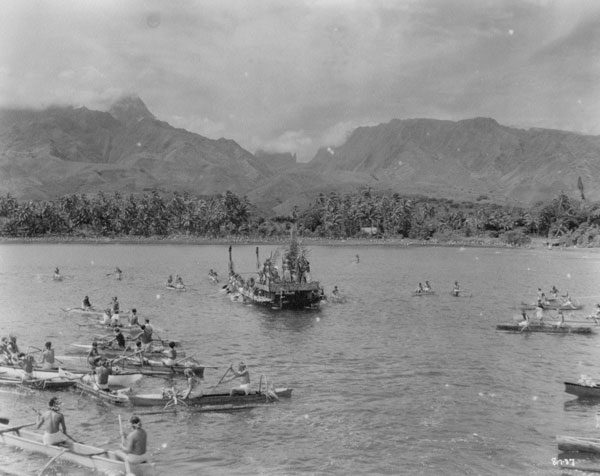

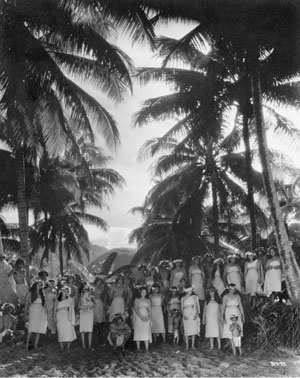

Frank Lloyd insisted on historical authenticity. Scriptwriters followed Nordoff and Hall’s novels quite closely. An expeditionary crew in early 1935 filmed backgrounds, villages and bays, searching for the perfect settings. Local filming June and July 1935 in the South Pacific involved the massive technical undertaking of shipping one hundred tons of valuable equipment (nine camera outfits, four very big generators, tons of film and more) the four thousand miles to Papette, Tahiti plus 50 technicians and the cast. Hundreds of uniforms were tailored to reproduce the authenticity of the 1790’s as well as costumes for the reported 20,000 Tahitian natives. Clark Gable complained that wearing knee pants and a sailor’s pigtail would not be manly and he balked at the idea of shaving off his “lucky mustache”, all intriguing publicity; historical notes showed that no facial hair was allowed in His Majesty’s Navy. Lloyd convinced Gable, with the gift of aCharles Laughton promotional tour around South America, of the need to get rid of his mustache.

Gable did, however, keep his American accent. Charles Laughton requested the Gieves Company, the very same London tailor that outfitted Captain Bligh a century and a half earlier and which still had Bligh’s measurements and type of material used, to reproduce the Captain’s uniform for the film. Charles Laughton lost 55 pounds in order to appear more “Blighlike” and to fit into the uniform that was based on those measurements. In one of the flogging scenes, Captain Bligh is shown reading from the “Articles of War”. Through research at the British Admiralty the exact book was found that ships’ captains would have had at that time; the British government printed two copies of that very same small book, one for the set and one as a gift to Frank Lloyd.

The film is a vividly realistic portrayal of life at sea.

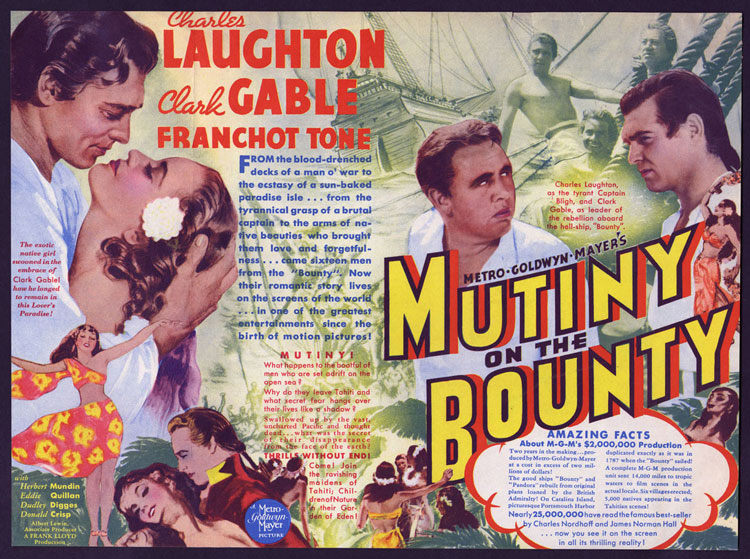

Lloyd valued Franchot Tone’s (as the humane aristocrat Midshipman Byam) understated professionalism and Clark Gable’s (as Fletcher Christian) delight with all things outdoors. Clark Gable, who had won the Best Actor Academy Award the previous year, portrayed the compassionate First Mate Fletcher Christian; with his inspired performance, he solidified his status as one of the leading actors of the 1930s. Charles Laughton disappeared into his villainous character (Captain William Bligh), enjoying the challenge, donning bushy eyebrows which were inspired by Lloyd’s own. Laughton, who had won the Best Actor Oscar in 1933, gave a larger-than-life portrayal of the cruel and arrogant Captain Bligh; he made the character one of the screen’s most memorable and abusive villains. Lloyd and Laughton developed into a mutual admiration society, enjoyed good Scotch together, invented a drink (“The Scotch Bounty”), followed each other’s career and would later reunite in the 1943 “thank-you to England” film, Forever and a Day.

Among the eight nominations that the film received, all three actors, Tone, Gable and Laughton were nominated for Best Actor; the film’s sole Oscar: Best Picture of 1935.

Interesting notes:

• Lloyd’s friend and fellow Brit, Herbert Mundin (as Smith, the nervous mess cook), supplies a grim dose of humor; the two worked on Cavalcade, Hoop-la, and later on Under Two Flags.

• Tough-guy actor Jimmy Cagney, another family friend of Lloyd’s, while sailing his yacht off of Catalina Island, saw the filming set; he asked if Lloyd had any work for him. Shortly after, he was in a sailor’s uniform, with a fake mustache and sideburns; Cagney spent the rest of the day playing a sailor aboard The Bounty. In 1945 they made Blood on the Sun together.

• Actor and Olympic swimmer Johnny Weissmuller, a few years into his Tarzan fame, paddled an outrigger in some of the scenes.

• Five hundred outrigger canoes and twenty-five hundred Tahitian natives added to the giant scope of the production.

• In the fourth week of filming on Santa Catalina Island, the prop peg-leg for Dr. Bacchus (Dudley Digges) disappeared, could not be found anywhere. A reward was offered but the wooden leg never surfaced.

Frank Lloyd considered the ship, H.M.S. Bounty, an important character, almost another actor. Copies of the original plans of The Bounty were obtained from the British Admiralty. Under the supervision of Cedric Gibbons, M-G-M Art Director, an authentic life-size replica was built at Los Angeles Harbor by a noted marine architect; christened and launched in 1934, the little ship sailed to Tahiti for filming. A second full-size copy, a stationary set, was shipped on two barges to Santa Catalina Island in California, where it was re-assembled in and around the town hall and used for interior shots and some deck scenes. In 1787, the actual 135 foot boat departed from Portsmouth, England with forty-four men on board on a two year voyage, refitted with a scientific mission to transport breadfruit from Tahiti to the West Indies as an inexpensive food source for plantation slave laborers. Dancing and singing, starvation and floggings, death and mutiny all happened on her deck, like a stage.

Here is a passionate toast, given by Midshipman Roger Byam (Franchot Tone), on his first cruise as a midshipman:

“To the voyage of The Bounty.

Still waters of the great golden sea.

Flying fish like streaks of silver,

and mermaids that sing in the night.

The Southern Cross and all the stars on the other side of the world.”

The production company spent eighty-eight days on location in Tahiti. Fog and tropical rain slowed down the filming, causing all to be alert and ready when the sun did come out. To pass the time in the evenings, the troupe put on talents shows, singing contests, dances in the mess hall, games and occasionally showed a movie. Both Franchot Tone and Charles Laughton were avid readers; Clark Gable made his own bullets for his rifle, shooting at sea-life off of the ship.

More than 600 cast and crew members were housed for several months on Santa Catalina Island. Six native villages were constructed on beaches on the island. The piers, docks and streets of England’s Portsmouth Harbor were also reconstructed there, at a cost of over $150,000. Athletes from UCLA and Compton and Santa Barbara Junior Colleges became extras, usually as oarsmen.

To advertise the film, M-G-M’s publicity department:

• supplied theaters with full-color lobby cards and posters

• provided study guides to high schools

• offered prizes for coloring contests for kids

• launched an essay competition for older students

“Why Did the Mutiny on the Bounty Change the Naval History of a Nation?”

• collaborated with book stores and libraries

• projected the 1935 one-reel documentary “Pitcairn Island Today”

• provided a 14-minute audio record with Bounty actors’ voices for radio stations

• also encouraged the playing of “Tahitian Love Song” music theme in theaters’ lobbies

• and posted an actor, dressed as a sailor and knotting ropes, at the theaters’ entrances.

Popular Science magazine advertised a model ship building contest with $1000 in prizes; the modeler received the kit by mail, sanded and painted it, assembled it, mounted the sails and riggings and submitted a photo of this 2-foot model of The Bounty to the judges.

Mutiny on the Bounty is the first major sound film to portray a storm at sea. Cast and crew used a windy, dark and stormy afternoon near Santa Catalina Island, filming on the stationary replica of The Bounty. As punishment for insubordination, Midshipman Byam is ordered by Captain Bligh to climb to the the very top of the main mast during the storm; Franchot Tone’s stunt double dramatically climbs to the top and ties himself to the mast. Equipment and cameras were tightly protected against the elements. Shortly after that storm second unit assistant cameraman Glenn Strong, attempting to save a camera from a sinking barge, drowned near San Miguel Island, the filming’s only fatality. A 27-foot model of The Bounty was fitted with buoyant tanks and an automobile engine by Buddy Gillespie from the M-G-M Art Department. In one of the last scenes of the movie, this brilliant special effect model was filmed running aground on Pitcairn Island (really the California coast) and then burning; this small model was later repaired and put on exhibition.

All over 600,000 feet of film went into post-production. The highly talented Margaret Booth, the first “cutter” to be called a film editor, demonstrated a keen sense about the flow of a film and worked very efficiently and quickly with Frank Lloyd, reducing the film down to 12,000 feet, about 132 minutes. Appropriate naval and patriotic themes were composed by M-G-M’s in-house music director Herbert Stothart.

Mutiny on the Bounty was the first remake (the first, Australian film, In the Wake of the Bounty (1933) starring Errol Flynn) to win the Best Picture Award at the Academy Awards. The film received eight nominations. It was one of the biggest moneymakers in the 1930s, returning a gross of $4,460,000 during its initial run. In 1951 the film was re-released and, to the dismay of film purists, in 1963 it was colorized.

For the November 1936 Photoplay Magazine, Frank Lloyd commented:

“When I finished reading Mutiny on the Bounty, I felt a definite excitement running through me. I knew I’d follow the simple history of a little ship – a character in itself – on a long journey. That aboard is a small group of men, courageous, sometimes sullen, always genuine. That the ship and the men reached Paradise and saw its beauty, were forced to leave that Beauty and mutinied. I knew that there, was thrilling adventure, a great and simple theme, the qualities of laughter and grief, and superb characters. And I knew that I could sell a combination like that to any audience.”